Work with Me

Applied research for mobility justice and urban design

I work with cities, organizations, and institutions navigating the human consequences of street design, mobility policy, and urban change across the Americas.

My work brings cultural studies approaches, urban ethnography, and historical research to questions of mobility justice and urban design—especially where technical solutions alone have failed to resolve conflict, risk, or inequity.

How I Work

This work is designed for decision-makers and practitioners responsible for streets, corridors, and public space—particularly where mobility decisions carry social, political, or equity consequences. In contrast to technical corridor studies, my approach draws on cultural studies to examine how power and assumptions embedded in design and policy determine whose movement is prioritized, whose risk is normalized, and whose safety is treated as expendable.

-

A deep, time-based analysis of a street or corridor as a lived, historical system. This work combines urban ethnography and archival research to understand how a corridor functions today by tracing how it has changed over time.

What This Work Assesses

Rather than focusing only on technical performance, this assessment asks:

How does this corridor feel to different users?

Who is expected to be here — and who is not?

What behaviors are encouraged, tolerated, or punished?

Whose time and safety are prioritized?

How have past planning decisions shaped present-day risk and access?

Methods

Urban ethnography (on-the-ground observation, walking and cycling the corridor, documenting lived experience)

Longitudinal archival research (maps, plans, policy documents, historical change over time)

Cultural analysis of mobility, power, and design assumptions

Deliverables

Deliverables are tailored to project scope, but typically include:

A written corridor experience report (PDF)

Ethnographic field documentation (photos, annotated maps, curated notes)

A historical corridor brief

Interpretive findings relevant to mobility justice and design

Optional public-facing summary or presentation

-

A focused analysis that situates a street, corridor, or mobility policy within its historical, political, and cultural context. Drawing on archival research and cultural analysis, this briefing helps explain how past decisions continue to shape present-day conditions — and why certain interventions succeed, fail, or provoke resistance.

This service is well-suited for projects that require context and clarity, but do not yet call for a full corridor assessment.

Use Cases

Preparing for corridor redesigns

Responding to public controversy

Supporting advocacy or grant applications

Background for journalism or reports

Internal decision-making and framing

Typical Deliverables

5–10 page written briefing (PDF)

Timeline of key historical decisions

Interpretive analysis of assumptions and power

Clear takeaways for policy or communication

Optional consultation or presentation

How I Read Meaning, Power, and Risk

Grounded Observation and Ethnographic Fieldwork

On-the-ground engagement with the corridor or policy context, documenting how people actually move, wait, cross, and adapt in everyday conditions.

01

Historical & Contextual Research

Archival research situates present-day conditions within longer histories of planning, policy, and investment.

02

Interpretation & Synthesis

Findings are synthesized into clear, usable analysis that complements technical studies and clarifies implications for mobility justice and design.

03

Applied Work: Interpreting a Corridor

A sample project that demonstrates how interpretive, ethnographic analysis informs mobility questions in practice.

PROJECT:

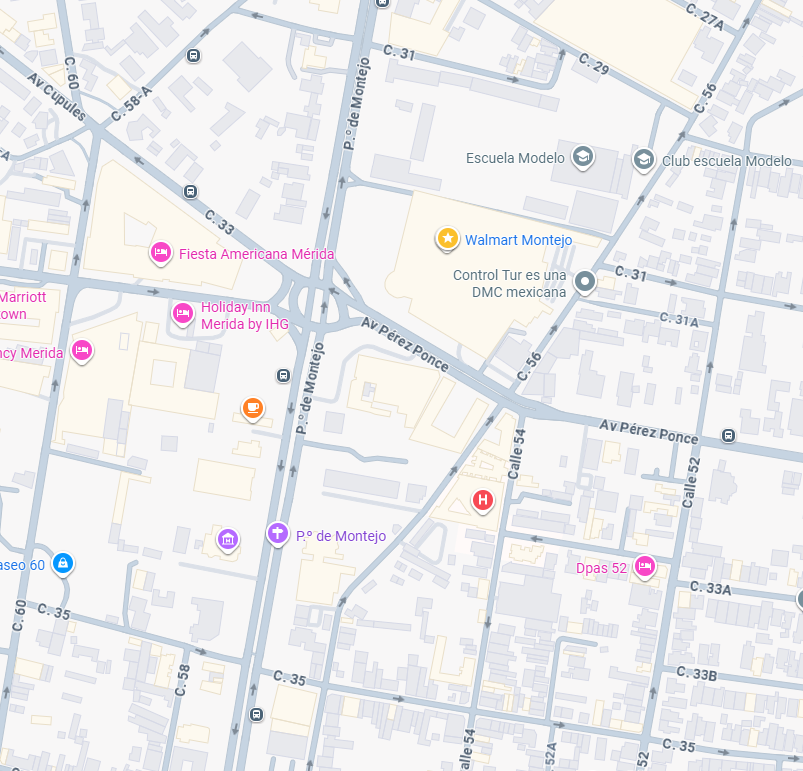

Reading a Corridor: Informal Bike Count and Ethnographic Observation, Mérida (December 2025)

Corridor observation area

This analysis draws on an informal bike count and on-the-ground observation conducted along a major arterial corridor in Mérida in December 2025. What began as a timed count of cyclists quickly expanded into a broader corridor ethnography, combining directional counts, sustained observation, and field notes documenting how people navigated a hostile and fragmented streetscape.

What I did

I conducted timed counts of cyclists during peak periods, alongside direct observation of rider behavior, pedestrian movement, transit use, and interactions with traffic and infrastructure. Field notes captured informal adaptations, moments of risk, and points of friction between design intent and actual use.

What I noticed

Although the corridor functions “efficiently” by conventional traffic metrics—high vehicle speeds and steady throughput—it is not meaningfully designed for any user.

There is no bike lane or safe cycling accommodation, despite regular bicycle traffic.

Pedestrians have no protected crossing points and must judge gaps in fast-moving traffic.

The median is narrow and offers little refuge. Pedestrians are forced to run across the street.

Bus stops incorporate hostile architecture, with no seating, shade, or safe waiting space.

People nevertheless use the corridor—by necessity rather than invitation. Riders slow, divert, or ride defensively. Pedestrians cross where they can. Most strikingly, people were observed climbing over hostile barriers near a bus stop in order to reach a Walmart directly across the road, effectively improvising a crossing where none exists.

What this reveals

Taken together, these patterns suggest a corridor optimized for vehicle movement while systematically externalizing risk onto everyone else. Safety is not absent by accident; it is redistributed. The design tolerates cyclists and pedestrians only insofar as they assume danger, delay, and physical effort themselves.

From a cultural studies perspective, this corridor encodes a clear hierarchy of value: speed over access, throughput over safety, and formal compliance over lived necessity. The presence of hostile architecture—combined with the absence of safe crossings or resting space—signals not merely neglect, but an assumption that certain users are out of place, or expendable.

Why this matters

This kind of applied analysis makes visible the gap between technical performance and human consequence. By documenting how people actually move, wait, cross, and adapt, corridor ethnography helps decision-makers identify where infrastructure is quietly failing—and where risk is being absorbed by those with the fewest alternatives.

Ready to work together? Hi—I’m Lisa L. Munro, PhD.

I study how power, risk, and everyday life shape our streets.

I’m the person decision-makers turn to when a street or corridor technically “works,” but feels dangerous, contested, or fundamentally misaligned with the people who use it. When traffic models say one thing and lived experience says another — when projects stall, provoke backlash, or quietly externalize risk, the problem is rarely a lack of data or technical studies.

My work focuses on that gap and helps decision-makers see what standard studies miss — before harm becomes normalized or conflict becomes unavoidable.. By bringing ethnographic observation, historical context, and cultural analysis to mobility questions, I help clarify how power, assumptions, and design decisions shape real outcomes on the ground — and why those patterns matter for safety, equity, and public trust.

Let’s talk about what’s happening in your city. Fill out the form to get started.